At Drury, the humanities consist of Languages, Literature, Writing, Film, History, Philosophy, and Religion. In literature, we teach students how to read and analyze texts (literature of all kinds, but also visual works such as graphic novels and film); in languages, students learn how to communicate with those who are not from their own culture, and they also learn about cultures very different from their own. In history, students learn not only what and how national and global events in the past took shape, but also theories of how to interpret those events, as well as how history shapes our current moment in time. In philosophy, students grapple with the questions of what it means to live a meaningful life, what is truth, what is ethical, what matters to them and why. In religion, students have the opportunity to learn about the long histories of their own religions, but also the histories of others, and what, for example, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam might have in common.

While the content is diverse, in all these disciplines we teach students a certain set of habits and skills to equip students to navigate an incredibly fast-paced information landscape. Misinformation is now pumped out via social media faster than we can keep up with it. The ability to read longer, nuanced writings has become less common. We also live in a precarious world filled with lots of hot takes and hot tempers: war, political strife, climate change, the ever-widening gap between the haves and the have-nots, a surge in racism, mass shootings, antisemitism, Islamophobia and more all have created an environment in which we need cool heads, individuals capable of deep reflection, careful thinking, and thoughtful strategizing. We need graduates from college not only to understand the world but to be leaders in it. This entails developing a set of practices for approaching complex contexts, texts, and arguments.

In the humanities classroom, faculty ask students to slow down, read complex texts from across centuries and cultures, pull them apart, think about what they mean, and engage with them deeply. We teach students how to think about argument and evidence: we talk about how to parse through complex sentences and complex ideas, how to unpack them, make sense of them. We talk about what an argument is, what it means to make a claim, and what counts as legitimate evidence to support that claim. We talk about the ways that multiple interpretations of a text or event are possible, as long as readers can draw on reliable evidence in support of a claim. We talk about not making arguments that are ad hominem.

While a student might be learning about the Civil War in a history class, verb conjugation and cultural traditions in a Spanish class, or the form of a sonnet in a literature class, humanities classes all teach students a shared set of practices and habits and ask them to enact these over and over again. Ideally, these become a set of dispositions or habits of mind: pause, read and watch closely and carefully. Unpack what you are reading, seeing, or listening to. Sit with it for a while. Discuss it with others. Pull it apart. Analyze it some more. Think about the claims that are being made. Unpack them. Do they have support? How do we know that what the writing (or film, video, documentary) points to as evidence is reliable? What claims might a student make in response? How might the student begin to develop her own argument, stake out her own thesis, support it with evidence, and sift through sources to determine what is reliable and what is not? We enact these practices regardless of what specific content in the humanities we might be teaching.

While a student might be learning about the Civil War in a history class, verb conjugation and cultural traditions in a Spanish class, or the form of a sonnet in a literature class, humanities classes all teach students a shared set of practices and habits and ask them to enact these over and over again. Ideally, these become a set of dispositions or habits of mind: pause, read and watch closely and carefully. Unpack what you are reading, seeing, or listening to. Sit with it for a while. Discuss it with others. Pull it apart. Analyze it some more. Think about the claims that are being made. Unpack them. Do they have support? How do we know that what the writing (or film, video, documentary) points to as evidence is reliable? What claims might a student make in response? How might the student begin to develop her own argument, stake out her own thesis, support it with evidence, and sift through sources to determine what is reliable and what is not? We enact these practices regardless of what specific content in the humanities we might be teaching.

Students in the humanities are prepared to not only live in the world after college, but to become thoughtful leaders in that world.

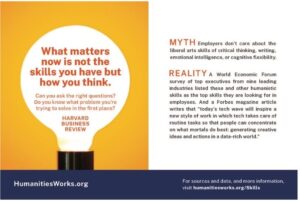

The Association of American Colleges and Universities’ most recent report, “How College Contributes to Workforce Success: Employer Views on What Matters Most,” a 2021 survey of nearly 500 executives and hiring managers from businesses. Here are some of the highest-ranking criteria these employers list as traits they look for in potential hires:

Students learn and practice these skills in the humanities classroom. We prepare students to graduate with precisely the habits of mind and critical thinking practices that employers say they are looking for in employees.

In addition, today’s college graduates will change jobs many times. They will need to learn new, technical skill sets throughout their lives. Technology changes quickly, social media and communication landscapes change quickly, needs for products and services and services pop up, die away, and new ones take their place. College graduates will need to show up to new places of employment ready to learn new techniques and strategies on the job. In other words, a student might need to create PowerPoint presentations in one job, write a white paper in another, and create a system of oversight in another.

In addition, today’s college graduates will change jobs many times. They will need to learn new, technical skill sets throughout their lives. Technology changes quickly, social media and communication landscapes change quickly, needs for products and services and services pop up, die away, and new ones take their place. College graduates will need to show up to new places of employment ready to learn new techniques and strategies on the job. In other words, a student might need to create PowerPoint presentations in one job, write a white paper in another, and create a system of oversight in another.

The temporary new skill a college graduate might learn in a particular job will change again and again, but the critical thinking skills, or the ability to learn how to learn, to deal with complexity, to analyze, and to respond, make up an evergreen set of skills that can serve as an undercurrent throughout a college graduate’s entire career. The skills they learn in the humanities—take on something new and intellectually challenging, analyze the problem or questions in front of you, break it into component parts, research it, develop a response, thoughtfully move forward with ideas of your own—these are portable skills that they will be able to take with them from job to job, and these will allow them to succeed in the workplace.

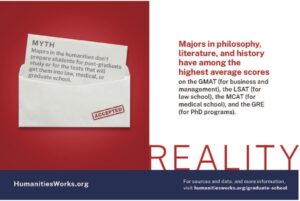

But, what about a salary you can live on? We can turn to data to answer this. One initiative out of Illinois, Humanities Works, has researched the data on college graduates in the humanities and provides some clear answers here. The claim that the English literature student will certainly be unemployed? Also not based on data, according to a recent study on employment status by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences. While the full report, The Employment Status of Humanities Majors, can be read by visiting this link, this chart from the report offers the results at a glance:

While study of the humanities allows students to live meaningful lives that include intellectual engagement, a lifelong appreciation of arts and culture, thoughtful citizenry, and knowledgeable leadership, it’s important to note that the humanities also prepare students for a range of jobs. The pace of career change at this moment in time can be supersonic. The underlying skills taught through the humanities: critical thinking, creativity, the ability to work with deep complexity, understand a range of positions and stake out and support one’s own decisions are lifelong skills that will allow students to navigate the many twists and turns in their career trajectories. The humanities allow for what we might think of as meaningful, long-term career resilience and growth.